Introduction

We’ve just announced this major transition for our little enterprise in the accompanying news item, and here we are telling you (much!) more about it. Most of the necessary background story about Cairn has already been covered in previous blogs, but I thought it would be useful to pull all the key parts of it together in in one place. Also, the readership for this one may perhaps extend to other people who may be interested in taking their organisations down the Trust route, so I’ve added little explainers here and there where the topics may be a bit more specialised.

Although this is indeed a big step, it’s actually a very logical further development of the way we do things here at Cairn. But perhaps more importantly, although it marks a very major transition, the intention is to allow us to continue indefinitely as a fully independent Company. This means that we can remain being here, for the continuing benefit of both our customers and our employees, without succumbing to the fate that has overtaken all too many of our (now often former!) competitors. So that’s WHY we’ve done it, but perhaps the more interesting question is HOW?

So that’s WHY we’ve done it, but perhaps the more interesting question is HOW?

To answer this, we need to go back to the very start of our little enterprise, and especially the principles on which it has been based. Although these principles are very straightforward, there is actually quite a tale to tell, which means that this blog is going to be longer than most, but also perhaps a little more interesting (or at least a little less boring?).

The ultimate irony here is that by setting up the Trust, I have just given the Company away to everyone else who is here now or will be at any time in the future, which sounds generous and perhaps in some ways it is. However, I have only been in a position to do so because it was all mine in the first place. And it was all mine for what could be viewed as rather selfish reasons, in that I just wanted to part of an organisation that let me do what I wanted to do, rather than what other people let me do.

As I shall shortly explain, before Cairn had come into being I had tried to fit into being a member of a much bigger organisation, but in retrospect I joined the wrong place at the wrong time. Those experiences made me realise that to do anything worthwhile in life, I needed to be in much more personal control of my activities! So when I decided that the next Company I was going to work for was one that I’d set up myself, it was going to be based on the following three fundamental principles:

1 No outside shareholders.

2 No bank or similar loans.

3 Own the freehold of your premises.

But if that wasn’t demanding enough, to this I ended up adding a fourth principle, although it was originally by necessity. However, it did give the Company a consequently very straightforward ownership structure, which from the point of view of being able to establish a Trust later on, has perhaps been the most important one., namely :

4 Do it on your own!

But please note, I am talking about how the Company came into existence, not how it has been for years now, as we couldn’t have got to where we are today without having become such a great team of people. There is therefore a huge paradox here! Although Cairn started as a single-handed operation, no Company with any aspirations to growth can possibly continue in that way. At some point you must stop trying to do everything yourself, and progressively hand things over to others. Hence for some years now my role has been one of Chairman, albeit with continuing active R&D interests, rather than being overly involved in day-to-day management. As the story develops, you will see that this transition was accelerated by the acquisition of our wonderful farm in 2001, but it needed to happen one day anyway. And hence our fifth principle, which may seem to contradict the other four, but is essential for a long term future:

5 Know when to hand things over to others

That doesn’t require you to disappear though, and instead I’ve concentrated more on the R&D side of things during the current farm era, as for reasons that I’ll explain further in due course, I consider the development of new products to be essential for the long term success of any Company like ours. However, this caused me to learn one principle the hard way, as a product that I was particularly keen to develop involved a collaboration. Of course collaborations are fine in principle, and indeed in many cases desirable, but as I shall also explain later, we ended up being the junior partner in this one. All very ironic in view of my otherwise constant striving for independence, and also all my fault, but it led to my appreciation of the importance of another principle, namely:

6 Make sure that you are always properly in control of what you are doing!

And right at the end of this blog, I’m going to introduce a seventh principle, which may perhaps be the most important of the lot, but meanwhile you’ll just have to wait (no peeping please!)

So to summarise, it’s been the combination of how Cairn used to be, compared with how we are now, that has made the transition to an Employee Owned Trust so straightforward. – or at least, when we met the right people to help us! But of course none of this would have come about if I wasn’t so dissatisfied by that previous existence from which the establishment of Cairn let me escape, and so that past is an important prelude to the story. It encouraged me to be ambitious enough to give all this a go, and more importantly, to do it with the principles that I’ve just laid out. Furthermore, Cairn was never intended to be a stepping stone to anything else, as instead I’ve always been playing for keeps, so of course that has also strongly influenced my particular approach to its establishment and growth..

So having set the stage, I guess I can now tell the story….

MARTIN’S EARLY DAYS

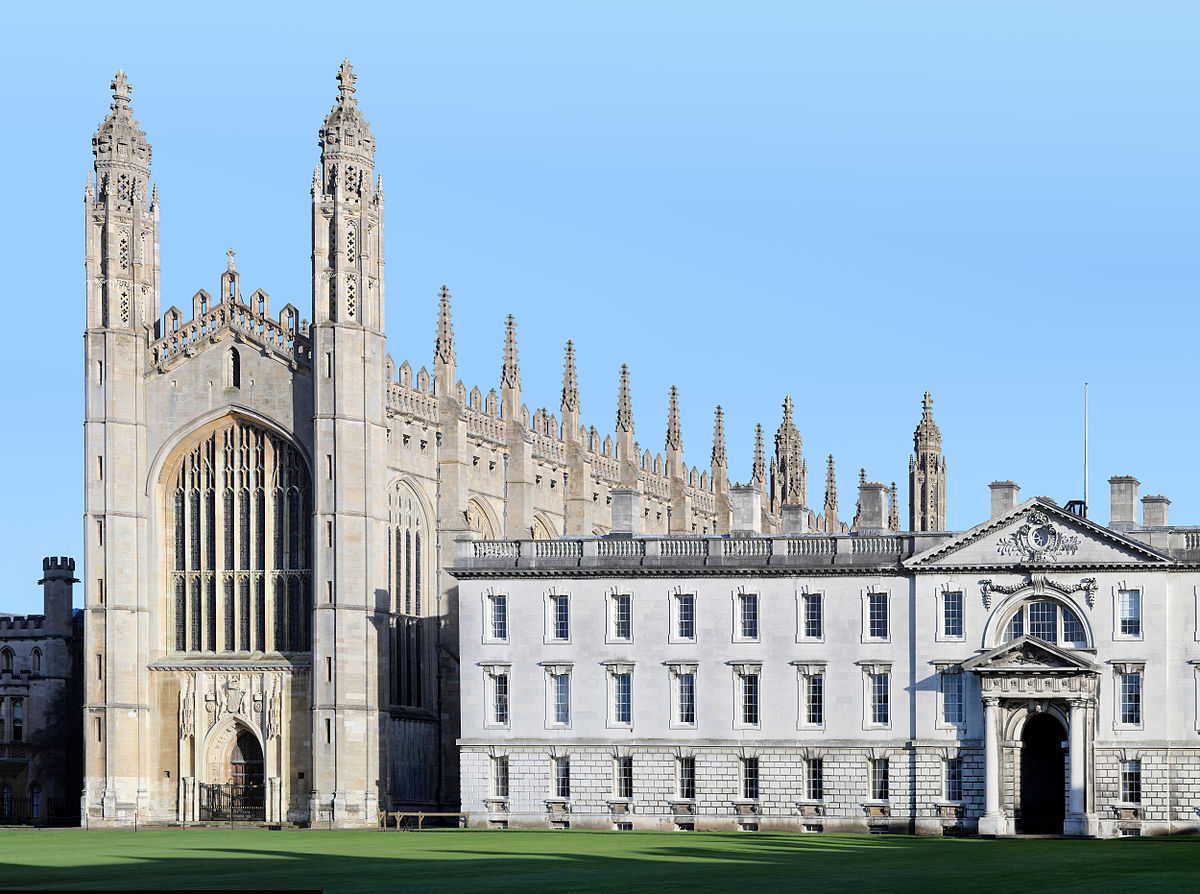

To do so properly, I need to go right back to the days of my upbringing in Guildford, as part of which I had to serve the necessary sentence at the local grammar school. I hated the place. The only possible escape open to me was to get into a faster stream that let me take my ‘A’ levels a year early, which allowed me to get the results before I applied to a University rather than afterwards. No way did I expect good enough results to get into Cambridge, but that’s what happened, and I enjoyed my time there as much as I hated that school.

Kings College

In fact I enjoyed it so much that although I wasn’t one of the truly gifted students, I nevertheless did well enough to stay to do a PhD, although it was one of those “prearranged” projects rather than one of my own choosing. As I already described elsewhere the project was simple and boring enough for me to spend much of my time doing other things, which mainly consisted of building all sorts of equipment, some of which was even used in support of the project.

But having not been marked out by anyone there for greater things, the question was what to do afterwards, and as I also explained before, the options I was encouraged to explore were more for the benefit of others than for me! So I said no, made a speculative enquiry of my own, and before I quite new what had happened, I found myself in Tony Gorman’s lab in Boston, where I was able to utilise both my technical and experimental interests to the full

But I only had a three-year visa, and in any case I wanted to return to the UK. However, most of the work I did in Boston hadn’t yet been published, and those same technical interests that had enabled me to so do much there, instead seemed to be counting against me when I was offering my future services to a variety of British institutions!

I was in any case wondering whether an academic future might be a little “dry” for me, and even if I got a tenured position for myself, the thought of having to keep a lab going via a succession of students and postdocs wasn’t a very attractive one. So that’s how I ended up accepting an offer from some research labs run by Shell just outside Sittingbourne in Kent.

Oh dear!

I had naively (and perhaps rather big-headedly after my American success) thought that with my ideas and their financial resources, it might be possible to do some interesting things there, and although the situation did look promising to begin with, successive management and policy changes meant that it progressively became clear that the limiting factors were actually THEIR ideas and MY financial resources! In fact, after one particularly major reorganisation I was effectively left with nothing to do at all for a year or two, which for a “doer” like me was especially frustrating.

Shell Research Centre

Sadly, around this time Tony Gorman died suddenly, and my Cambridge PhD supervisor (now also long dead, so I can tell it like it was!) never really showed any interest in me, but hey, that’s Cambridge for you! So this left a shortage of decent referees for future job applications, and also my inability to achieve anything of significance at Shell, plus the growing impression that the days of that institution were definitely numbered, meant that I was not at all well placed to find decent employment anywhere else – as essential as that was clearly going to be.

A CAIRN TAKES SHAPE

So that’s why I became so strongly motivated to set up Cairn! I have already related that during this crazy period I had been able to save at least some of my sanity by helping someone get an audio amplifier company off the ground, but that he was only interested in having me join him as an employee rather than a business partner, so that wasn’t going to be a long term option. However, it did provide some useful insights into the potential trials and tribulations of running a small business, and which turned out to be very useful when I took the plunge.

As to what Cairn was going to do, in retrospect it was so obvious that originally I was planning to do something else, but which was more in the area of domestic electronics, where I soon realised that I just didn’t have any useful contacts. In fact, that origin is where the name came from, because in those very early days I did have a business partner (Andrew Thompson, a fellow escapee from Shell), and who I’m pleased to say remains a friend! We wanted a name for the Company that would let us do practically anything, rather than being associated with any particular activity, Andrew rather liked “Cairn”, and from my perspective it would let us use some nice scenic shots like the one below for our publicity material, so that was that!

However, Andrew also had other interests that he preferred to pursue, so I soon bought him out, which left me as just described, namely on my own. This was accompanied by the logical change in direction for me, which was to commercialise some of the equipment I’d designed and used during my years in Boston. Here I did have a ready market, as the work I did there was much better known to my scientific contemporaries than to the people who tend to sit on appointment committees – and I must say that is a situation that has served me VERY well!

So what exactly were we going to sell? During my Boston days I needed to make sequential but rapid optical measurements at a range of different wavelengths, which I achieved by putting a series of optical filters in a wheel that I then span very fast. As basic background, I should explain that this was for the measurement of calcium ion concentrations in nerve cells, using the optical absorbance indicator arsenazoIII. By the time Cairn came into existence though, that method had been superseded by indicators that worked by fluorescence instead, but a popular one of these, named fura2, also required to be sequentially illuminated in the same sort of way. So there was both a potential product and a potential market, and in some respects all I needed to do was not to mess things up.

FIRST SALES

And for trying not to mess things up, one of my tricks in life has been to try and put setbacks to my advantage. In this case it meant that although the Shell labs seemed unlikely to have a long term future, there was no need to jump ship just yet. I now knew what I was going to do, and to keep the Shell job while I got Cairn going on an initially part-time basis avoided the need for any external finance. Also at this time (mid 1980s), I was actually on secondment to a lab in Leicester, where the atmosphere was much more positive and convivial, so in practice it was a rather enjoyable period, albeit a very busy one!

As an (again in retrospect) amusing aside, and to show that I was also still trying to pull my weight at Shell, this contrast led me to suggest that if they wanted to make their research more cost-effective, they could perhaps consider establishing a few smaller and more or less independent groups at universities or similar outside institutions. However, all that happened was that I got an albeit not too serious dressing down for circulating this suggestion rather too highly through the Company hierarchy, as opposed to putting it through the “usual channels” but at least the higher-ups got to see the suggestion this way!

It was during this period that we made our first sale, which was a spinning filter wheel system together with some electronics to sort out the signals from the individual filters. What I actually did at this point was to design a modular system to which extra components could be added later. This allowed a basic system to be supplied straight away, and for which those extra components would become available just as soon as I’d designed them! It got money into the business at a much earlier stage than if I’d tried to complete everything first, and it also allowed customer feedback to be incorporated in the subsequent developments.

By the time my secondment finished (autumn 1987), other orders were in the offing, particularly a very large one to Italy, which had been passed on to me by another Company who wanted to share in the further commercialisation. However, that was derailed by a reorganisation there, which left me doing it all myself – pretty hairy at the time, but also a blessing in disguise! By the way, one of the good things about the Shell job (there were a few) was that you could do whatever you liked in your own time if it didn’t conflict with your daily responsibilities, so none of this needed to be secret. Therefore (early 1988) I was able to take on a local friend (Adrian Hawkes), who had been temporarily incapacitated from his previous job by a nasty footballing accident, to help move things along in the house while I was doing my own day job.

To my relief, the Italy order was successfully completed and installed, and with other business coming in, it became clear that Cairn would soon be strong enough for me to go full time. But I also got a salutary warning! Delivery of one order was delayed by a full six months because of a very late delivery form another Company, but my continuing Shell salary meant that this was just an inconvenience rather than a problem (and luckily the customer could see it wasn’t our fault), so from that lesson I decided to hold on there for as long as I could.

One other thing I should explain here, and again to my no small amusement, is that I do like to do whatever I do properly, which means trying to get to grips with the details as well as the basics, since getting either wrong can kill you. So at Shell I managed to acquire the reputation of an esoteric scientist rather than someone with his feet on the ground in the real world. That such a person could run a successful business was of course unthinkable, so they never took Cairn seriously (and hence weren’t bothered about it) until the day I was finally ready to say goodbye!

Those labs closed down just a few years later, hence I’ve been able to say that they just couldn’t cope without me, although in the interests of fairness I also point out that they couldn’t seem to cope with me either. After some admittedly early promise, as time went on I’m afraid I found it an increasingly and demotivating place to work, so I vowed to do my best to make Cairn different. I have learned from both sides of this particular coin that people are much more productive when they are happy and feel valued!

SPINNING WHEELS IN A COTTAGE INDUSTRY

That departure “day” was Easter 1989, and with me now full time the business took off like a rocket! Going back to those principles, well for the first principle the only other shareholder had been Andrew, who was internal to the business but soon to withdraw as previously noted. I had built enough savings to finance the business myself, thereby meeting my second principle. And in any case, the first of my many bank managers did offer a loan, but only if I gave a personal guarantee, to which I of course replied with thanks but also explaining that it therefore made more sense for me to use my own money anyway. For the third principle, namely to own your premises, well to begin with the business was just based in my house. And for the fourth principle, apart from Adrian’s help with building things, I really was doing it all myself!

For the next couple of years, we were therefore able to do a lot of business with very low overheads, but this did NOT deter me from selling our products at what I considered to be the full market rate. Since I was determined for Cairn to grow, I wanted to prepare for a day when we would have more employees, proper premises, and all the other trappings that go with a fully established little enterprise. Therefore in pricing our products, I based them on what they should have cost us to make, rather than what they actually did. But in comparison with whatever else was around, the prices were nevertheless very competitive, so there was no shortage of takers.

Also, the modular nature of this system – of which we still sell a few from time to time even now – meant that people could buy a much or little as they wanted, and they could also use it to extend the capabilities of other equipment they already had. But the heart of it was that spinning filter wheel, so if Cairn was becoming famous for anything, it was for that. I’ll say more about our filter wheels later on, as although sales of such systems did eventually pretty much cease, having subsequently been replaced by a different (fast monochromator) technology, more recently the sales of our latest filter wheel design have been going through the roof. So at the risk of making yet another of the weak puns for which I am all too infamous, our involvement in such products really has gone full circle.

But meanwhile what we now call our “first-generation” filter wheel systems were doing us proud, so in the summer of 1990 James Kerin, who was then another local neighbour, joined us. You may recognise the name, as he is still with us, now being our Marketing Director. but in those days all three of us were building things pretty much full time. Clearly our days in the house were now numbered, but we were also making enough money to be able to move on.

FIRST PREMISES

Yes, by the end of 1991 we had made enough money to buy our first premises outright. Hence our third principle, of owning your premises, but without breaking the second one of not borrowing any money, was very thoroughly sorted! It was a fairly standard “starter” unit of about 1,000 square feet in those funny British measurements that we’ve always stayed clear of for our Cairn products, but the roof height was just enough for us to put in a full intermediate (“Mezzanine”) floor, which effectively gave us almost double that space. I was greatly assisted here by a local builder and steelworker by the name of Silvano Richards (generally known a Sav or Sam), whom I had met in connection with carrying out some extension work to my house, who made a very impressive job of this, and who will feature again as this tale develops.

This development meant that it was now time to move yet further away from that fourth original principle of doing it all yourself, as we now had space for more people! Jez Graham (now our CEO of course) joined in early 1992, and a chance meeting in a local hostelry led to Dallas Rush (also still with us as a production engineer) joining us a few weeks later, so then we were five! Actually the Dallas “story” has been one of the most personally satisfying aspects of the whole Cairn saga. He had joined the audio and TV company Rumbelows straight from school at the tender age of seventeen, and after seventeen years there he had just been made redundant by the closure of their service department. So it was nice for Cairn to be able to offer him something instead, but that was now nearly thirty years ago! The fact that an upstart little Company like ourselves can offer longer-term employment than a supposed “major employer” could is a source of great pride as well as bemusement!

Compared with just a spare bedroom in my house, we now had oceans of space, but it pretty soon filled up. Andrew Hill (now Technical Director) and Neil Sims (now Production Director) joined us in 1995, and Wendy Jones (now Finance Director) and Dominique Rogers (now optics specialist and ISO guru) came on board soon after, so that space was soon being used to the full. These premises were in a former shipyard in Faversham, and although the immediate surroundings weren’t the greatest, we had a super view of the local waterway (Faversham Creek) from our newly-installed upstairs windows, and Faversham itself is a really smashing town with a genuine centre to it, so we were very happy there. But as we continued to grow, we realised that we couldn’t stay there forever….

FINDING THE FARM

By the late 1990s those originally rather generous premises were becoming increasingly cramped. We definitely needed somewhere bigger, but what and where? We very much wanted to stay in the Faversham area, but the options were limited. For a while we had an eye on some nearby premises, but it was never clear whether or not the owner actually wanted to sell them. Also they were towards the end of a one-way street, with limited passing places for oncoming traffic, which would never have worked for the traffic levels that Cairn has now! However, in the summer of 2000 we managed to find a one-third of an acre site on which we could design and build our own larger premises, and so I left for one of my American holidays in a very happy state of mind.

Only to find on my return that it had all fallen through! We then looked at another potential development site several miles further away, but it didn’t look as if anything was going to happen there any time soon, and it didn’t really appeal to us anyway, so we had no choice but to leave things for a while. However, with the arrival of the following spring we embarked on a concerted further effort, which involved a thorough scouring of potentially available local land or property.

Which is how I found the farm! It appeared in a relatively small advert in a local paper that was primarily devoted to Sittingbourne rather than Faversham, so we could easily have missed seeing it altogether. Initially it didn’t look at all promising, as at half a million pounds it was way beyond our budget, and apart from a farmhouse and some 47 acres of land, it wasn’t at all clear what was actually there. However, by now we were so desperate that we thought we should at least take a look.

I still recall the mix of emotions when I saw the place. The house needed a huge amount of work, but it formed the bulk of the total purchase price, so if I sold the house I already had and bought the farmhouse personally, then we would have enough to buy it all. And as well as the land, plus some stables that were in relatively good condition, our money would also get us some very sad and sorry looking outbuildings. These looked a far cry from the pristine new building that I had been dreaming of for Cairn, but if we could get permission to convert them, then we might just get the purchase to work.

But talking of work, this would involve a huge amount, which I wasn’t looking forward to at all, but on the other hand it was an opportunity I couldn’t refuse, so when the local Council indicated that permission was likely, my fate was sealed!

To say that the acquisition of the farm has been transformative would be an understatement, so here our third principle (“own your premises”) has served us better than we could have dreamed of, which will become increasingly clear as we continue the story. At the time though, we were pretty sure we were going to be outbid, as surely we weren’t going to be the only people to spot the farm’s potential. Except that we were. Such places were very out of fashion then, and in the words of the agent who sold it, which have been ringing in my ears ever since, “Nobody wants these small farms nowadays!” Well, a lot of people do want them in the current nowadays, but they certainly aren’t having ours!

But clearly, purchasing the farm was just going to be the start, as a great deal of further money as well as time was going to be needed to convert the outbuildings into somewhere that would be suitable for the business, plus there was that big old house to sort out as well. On the advice of our accountants I’d bought our shipyard premises personally, so assuming I managed to sell them (which I did), that would help with the cost of trading up to and refurbishing the house (which it indeed did).

In fact, here is a salutary lesson for keeping down your business overheads! We only made a relatively small profit on the shipyard sale, compared with the purchase price and the cost of putting in the extra floor, but the real “profit” was a decade of Cairn not having to pay any rent for the privilege of being there – which pretty much covered the purchase price. It’s “tricks” like this that really make the financial difference!

WHOSE PENSION FUND IS IT ANYWAY?

Even so, we had taken on a very serious project, and here we were helped by a decision I’d made when I left Shell. One of the possible perks of being a Shell employee was a relatively generous pension fund, and any financial adviser worth their salt would surely have recommended that I left my pension contributions with them, but I wanted to feel that I’d make a complete break, so I took them with me and reinvested them instead. I also had the feeling that it might be possible to put the money to good use before it was needed as a pension, which of course I couldn’t do if it was still in the Shell fund.

That turned out to be correct, as it was possible to use the fund (which had grown nicely meanwhile) to buy the farmland and outbuildings, so Cairn’s hard-earned business profits “only” had to pay for the albeit substantial conversion work. Therefore we could do this without breaking our second principle (“No bank or similar loans”). And perhaps more usefully, this has made us more immune from the business “being taken to the cleaners” by anyone, since it means that the pension fund rather than Cairn owns the land and buildings, thereby providing a nice financial bulkhead between the two operations. That’s particularly handy, since as previously noted, changes in both financial and lifestyle values over the last couple of decades have made the farm a much more desirable property than even we could have envisaged at the time.

That pension fund ownership will continue to be the case even in this new Trust era, so I haven’t given everything away yet! Needless to say, the rules concerning pension funds are both complex and relatively restrictive, but that is also potentially to our advantage. I have no need to draw on the fund for the foreseeable future, as I am still gainfully(?) employed by Cairn and have other assets anyway, and the regulations allow the fund to be transferred to the Trust as a legacy, for which the arrangements are already in place. So ultimately the Trust WILL own everything, but not just yet!!!

DEVELOPING THE FARM BUILDINGS

One thing that we regular bore our visitors with is the “before and after” photos of those farm buildings, of which you can see one or two here. As I would often have to explain to the people doing the conversion work, it would indeed have been cheaper to knock them down and start again, but we would never have got permission to do that.

The other problem was that the total area of the buildings that we got permission to convert wasn’t that much greater than that of our previous premises, but we had hoped to link them together to provide a significantly greater overall space. However, it turned out that the local Council didn’t like that idea at all, and could only countenance some sort of “linking corridor” between them. But then one of the planners suggested that if we wanted to have more space, we should instead apply to convert a third building on the site, which made sense because the proposed corridor could be extended to include that as well. What seemed to make less sense to us was that this “building” was just an asbestos-clad concrete-framed barn, but who were we to argue? We were told we had to keep the asbestos though, unless it was in any way disturbed during the conversion, which it actually had to be, and so practice it had to be removed. Hence in this case we DID pretty much end up with a new building, as only the concrete frame survived. The moral here is that apparently pettifogging regulations can sometimes be your friend as well as your enemy!

The conversion work was going to be a major operation though, so how to organise it all was another potential problem to deal with. However, knowing what a great job Silvano had made of converting our shipyard premises, I knew who to call. There was much steelwork as well as regular building work to do, so he was the ideal person to help us. I’m not sure if he’s ever really forgiven me though, as it was much more work than he really wanted, but we have nevertheless become firm friends!

Between ourselves we also managed to avoid making any silly design mistakes, which put us well ahead of my experiences of new buildings in my Shell era. There was a particularly lovely one where they’d put the air intakes in one new building right next to the air extracts, which encouraged a certain amount of “recirculation”. Not at all funny at the time though, as before this was realised, I got the blame for stinking out the building when I was doing something smelly! I’d been trying to take the initiative on something, but that turned out never to be a good idea there….

All this, combined with knocking the farmhouse into reasonable (and also now very nice!) shape took a couple of years after our purchase finally went through in autumn 2001, but it wasn’t until autumn 2003 that our respective new homes were ready to move into. This was actually a very stressful time, since in addition to my organising all the building work, my mother’s health was failing (which was a double problem as she had been nursing my sister who was also in poor health), and a clearly jealous neighbour was trying to give us a hard time over some other planning issues. It never rains but it pours!

So that meant I needed to adopt that fifth principle, namely handing the running of the business on to others, some years before I had expected, as all these other issues were taking up far too much of my time and effort. And once I’d handed over the reins to Jez, it would have felt a really retrograde step to ask for them back again, plus there was more than enough else for me to get on with, as I shall shortly describe. Running the business on a day-to-day basis had been surprisingly fun, bearing in mind that what I most enjoy is designing and building things. But I think an important reason for enjoying the daily responsibilities was because of those previous experiences. By being in charge I had the freedom to do what I wanted on the product development side, and this had felt like a pretty fair exchange to me.

YET MORE FARM WORK!

Although it may sound as if the farm work was finished by 2003, in fact it has taken up a fair proportion of my time ever since! The farmhouse needed a proper garage instead of the prefabricated monstrosity we’d inherited, so I took the opportunity to put up something more generous, with a big upstairs workspace from where I’m writing this now.

Also near the farmhouse were a couple of brick-lined tunnels going into the hillside, and which were apparently used to grow rhubarb – from which we can only conclude that either creating such tunnels was very cheap or rhubarb was very expensive in those days! They needed a bit of renovating too, and we were also able to convert an adjacent furnace area (it looks like the tunnels were once heated!) into a yet further garage.

The farm also included a fairly comprehensive stables area as previously noted, which although in better condition than the house or the outbuildings, could certainly benefit from some attention. This was especially to replace the old asbestos roofing with something better looking and more environmentally friendly, so I found myself looking after that too. It’s all being further renovated as I write this, as much of the woodwork now needs replacing, but the buildings themselves are all very sound. And talking of sound, one is currently being fitted out as a radio studio, but that is DEFINITELY another story!

And in 2009 we bought another 23 acres that had originally been part of the farm. This included a natural spring and a watercourse, and we landscaped part of it to make a nice wildlife refuge, including a couple of ponds. We managed to buy this relatively cheaply too, as independent access to it was very poor, whereas it directly adjoined our existing land. In fact it had previously been owned by our troublesome neighbour, but it needed to be sold as part of a divorce settlement (and to whom we are therefore indirectly grateful), so now we had a total of 70 acres to ourselves!

But now back to the business side of the farm! By 2013 Cairn had grown to the point that we saw we’d soon need yet further space, so now it was time to turn my attention to that too. Another of the great benefits of having the farm is that it gave us ample space into which we could potentially expand, and for which our local Council were very supportive, so permission for a nice new building was duly obtained

Once again this was financed by retained profits, although it ended up costing a fair amount of money, as we fitted it out to a pretty high standard. However, we were able to spread the work out over several years as we didn’t need the new space straight away, so it was 2018 by the time that building fully came into use. Actually, when I say “a fair amount of money”, this was only by our standards, rather than the amazing sums that others seem to spend when they put up a new building. I had fun with this in one of my blogs, in which I argued that we must be doing something wrong by spending so relatively little to obtain so much useable space!

So one way or another, looking after the farm has proved to be a job in itself, albeit also a very satisfying one. However, although my day-to-day management activities have pretty much had to go in order to support this one, there has still been time for me to continue my product development interests amongst it all. Although some of these have come out pretty well, there was also a lesson that I had to learn the hard way, giving us our sixth principle, as you can now read!

LEARNING A LESSON THE HARD WAY – STAY IN CONTROL OF WHAT YOU ARE DOING!

As part of becoming rather less single-minded in my approach to business, I felt that once we’d secured our future on the farm, it would be good to develop at least some products jointly with other organisations, rather than being TOO fiercely independent. In fact, such collaborations have become a major activity for us, but only because the others here have been rather better at choosing them than I was! In some ways I’m reluctant to get into this story at all, but in the interests of providing a warts-and-all account I really can’t leave it out. For obvious personal reasons I shall need to tread gently though, so I’m telling the tale in a general sort of way, but I do regard the whole thing as being very much my fault, resulting in much wasted personal and Company effort, although there is still a chance of something coming out of it all.

The story started around the turn of the century, when we heard of a group using digital multimirror devices (DMDs) in microscopy, not just for controlled patterns of illumination, as they are in video projectors, for example, but also for confocal detection (for nontechnical readers, this is a method for rejecting out-of-focus light in a microscope image, so that you instead see a series of infocus images as you focus at different depths into the sample). But what really what got my attention was that they had devised an optical system using a second camera to image the light that was rejected by the confocal detection process, and which also contained useful information for improving the image quality. I thought that was really neat, but the idea had been patented and so I had expected it to have been further developed by others.

To shorten a long story, when I later enquired about the project’s further progress, it turned out that a patent licence was going to be available, but that it would be part of an overall collaboration agreement for joint development of a commercial product. The agreement was generous but I hadn’t realised the extent to which it would nevertheless tie our hands. The real problem turned out to be that our collaborators had become disenchanted with DMDs, specifically citing their apparently huge diffractive losses, so we were persuaded that devices based on liquid crystal technology would need to be used instead.

We should have walked away then, but unfortunately in retrospect, I could see how they could be made to work in a similar way with two cameras, so we went ahead. However, since the original researchers in our collaborator’s lab had all moved on, we were effectively left to do the major development work ourselves, but critically, the liquid crystal devices turned out to have problems of their own, in respect of both efficiency and image contrast. Of course this couldn’t really have been known in advance, but the most annoying feature of this whole story is that given a free hand, we wouldn’t have looked at the things in the first place! But it wasn’t our decision….

If this had been a more informal collaboration, it would soon have changed direction or ceased entirely, but we were locked in by that agreement, in which we were the junior partner because it wasn’t our patent. In consequence things dragged on for longer than was really sensible, and the situation was further complicated by the collaboration also becoming part of an EU grant. The collaboration did eventually end though, albeit in a way that allowed us to continue to develop an instrument ourselves if we wanted to.

But thanks to my (at least in retrospect) misguided enthusiasm, we had spent a lot of time and effort for little or no return, so I cleaned up as much egg off my face as possible and we turned our attention to more productive and profitable development activities for a while. However, a few years later we were looking for a project for a summer student, so we thought we’d have one last look at this just in case anything could be salvaged. The simple answer for liquid crystals was no, but the more complicated one was that when we cannibalised a DMD video projector for comparative purposes, we found that the diffractive effects of these devices were actually quite manageable if we increased the system apertures somewhat, and we could also see a way to get around some other problems of the original optical design. So we were now back in business, albeit progressing much more slowly, since from our previous experiences we literally weren’t going to bet the farm on the thing!

Hence we do now finally (a mere couple of decades after hearing about the original work) have a product after all, which we call the Cairnfocal. It’s a nice piece of hardware, but of course it needs some matching software to drive it, so the few sales we’ve made so far have been to people who can help with that side of its further development. However, the ultimate irony is that this has all taken so long that the patent has now expired! Actually that’s quite handy as it does avoid the need for royalty payments, and to be honest we don’t think that the market is going to be big enough to encourage any competition.

But the moral of this sorry tale is that we would have got there much sooner if we’d had proper control over the project, and the fact that we didn’t was all my fault.

Of course, this disappointment was tempered by my involvement with successes elsewhere, especially with the development of our range of image splitters, which allow two, three or even four different images to be displayed on different regions of a single camera, and also with the optical designs for connecting multiple cameras to a single microscope. I’ve also been mostly responsible for our LED illumination systems for microscopy (apart from our very nice Aura phase contrast system), so on the whole I’m not feeling too bad about things.

However, there has been one other project that has taken up a lot of my time in more recent years, and which is now finally proving its worth. I think it’s a nice example of the sort of thing that a Company with our principles of independence can see to fruition, whereas in a more “conventionally” run organisation it would surely have been axed long ago. Thanks to the establishment of the Trust, I hope we can continue to persevere with what turn out to be the more “challenging” projects, but even for Companies like ours, there have to be limits, so there can still be a question to ask, namely….

WHEN TO PERSEVERE, AND WHEN TO PULL THE PLUG ON A DEVELOPMENT PROJECT?

I still don’t know.

But there can nevertheless be a few clues! The technical issue with the confocal microscopy collaboration was that liquid crystal technology turned out to be unsuitable for the type of product that we were trying to develop, and nothing could fix that. But in the example I’m dealing with here, the technology we had chosen was perfectly suitable, and instead the problems we encountered were engineering ones, so here the question was whether we could fix those.

And the product in question is particularly close to our hearts, as it’s our latest-generation filter wheel. Or more correctly, filter wheels, as our Optospin product is now also available in a version accommodating 32mm rather than 25mm diameter optical filters, and with a 50mm version waiting in the wings. And since so much of the Cairn story has “revolved” around filter wheels, we may as well summarise the whole story again here.

That first wheel I made in Boston needed to spin very fast, at around 20,000rpm or so, in order to make the sequential measurements at different filter wavelengths to be as effectively simultaneous as possible. This was actually quite simple to achieve, by blowing a jet of compressed air at the edge of the wheel, but of course the speed control for such a system was relatively poor. That didn’t matter at the time, but clearly for applications that didn’t require such high speeds, some form of electrical drive would clearly be a better way to go.

Therefore, on my return to the UK I made a simple electric version that used a drive belt to couple the motor to the wheel (that’s the blue unit in the photo, to the right of the original compressed air one). Together with being able to bring pretty much a duplicate set of electronics back to the UK with me, this allowed me to have a kind of “travelling roadshow” for bringing along to various labs with me, and which therefore served to remind the outside world of my continuing existence during that strange Shell era. By the way, one of the other things I did at that time was to write a book (Techniques in Calcium Research, Academic Press, 1982, ISBN 0-12-688680-6), which included descriptions of both these early versions of the system. Little did I realise that I was writing about the future as well as the past!

The first Cairn filter wheel (third along in the photo) was basically a derivative of that first electric design, but with a kind of clock escapement mechanism that also allowed it to be stepped, albeit slowly, from one filter position to the next. After a few years it was replaced by something more sophisticated (fourth along), which could be stepped more rapidly and controllably, but all these wheels had used relatively small filters of just 12.5mm overall diameter. That was fine for selecting illumination wavelengths, but there was an increasing need for wheels that selected the detection wavelengths, which meant that the filters had to be big enough to transmit images to a camera.

That generally requires filters of at least 25mm diameter. Continuously spinning a correspondingly larger wheel is no problem, but the laws of motion mean that it’s much harder to step discontinuously between filter positions as quickly, for which a much more powerful motor is needed

The fifth photo shows our first effort, in which the wheel was effectively its own motor, with coils around the outside of the wheel interacting with magnets around its edge in order to drive the wheel around. Unfortunately this made for a design of inconveniently large diameter, and it was all but impossible to set up, so this approach was soon abandoned.

Then we came across a range of compact, low cost and powerful motors, that had been developed for driving electric model aeroplanes, and their characteristics looked ideal. Although designed for continuous spinning, they were also powerful enough to move the wheel rapidly but discontinuously between any filter position. Also their small size allowed a very nice dual wheel configuration, in which two wheels overlapped as explained here

However, as also explained there, controlling the discontinuous movement proved to be a nightmare, but the sixth unit in the photo shows the ultimately (very!) successful result. For this sort of application, something called a “stepper motor” is normally used, which actually rotates by making a number of more or less closely spaced angular jumps. Hence it’s a relatively slow process for large angles, and is even less suitable for the continuous spinning mode that we also wanted to support. However, with this type of motor it’s much easier to precisely reach and then hold a given angular position, whereas with “our” motors we were much more on our own!

In summary, what we wanted to do was technically feasible but an engineering challenge, and it’s fair to say that I hadn’t fully appreciated just how big a challenge it was going to be. In a less independent Company than ours, I’m sure my bosses would have just cancelled the project sooner or later, but I knew I was making steady enough progress for it to be worth continuing. And of course a fair amount of “out of hours” work gets done under such circumstances, which is much more likely to happen if you are genuinely in control of things (ah, that sixth principle again!). Compared with our first results, the Optospin in operation looks pretty much looks like magic to me, but of course it isn’t – just the result of lots of hard work! And a lot of that work was really rather fun! And the best way to ensure that things can stay like this for the long term is by….

SETTING UP THE TRUST

Although the Cairn Research Employee Ownership Trust only came into existence a few days ago, in October 2021, the possibility had occurred to me years before. I began to look into it more seriously in 2014, with this latest attempt actually being “third time lucky”. So I hope the information I am giving here will make the process easier for anyone following in our footsteps than it was for us – although we got there very painlessly in the end.

I should first explain that the Trust model is a collective ownership one, in that all the shares are held by the Trust itself, but the dividends from declared profits are distributed amongst the employees. Therefore everyone is effectively a shareholder for as long as they are employed by the company, but they don’t take any shares with them when they leave, which allows the Trust itself to continue to have full control for the long term. And the Trust is administered by a Board of Trustees, who are themselves generally employees, with at least some of them chosen by other employees, so that the business is run for the benefit of everyone.

Furthermore, a Trust like ours can never really be sold, and instead our main possible “exit” is to be wound up with the proceeds going to a designated charity. This therefore makes us immune from being taken over by the corporate or venture capital giants that seem to increasingly dominate our business sector. Marketing Director James and I consider this to be “marketing gold dust”, since unlike the fate that befalls (or has befallen!) so many of our competitors, it means that we’ll still be here in years to come, when that once shiny new equipment now needs a bit of loving care to get it back into action for you!

By the way, although the important concept is to keep the Trust itself intact, it can nevertheless invest in other activities if it wants to, so it’s not the straitjacket that it might otherwise appear to be. In fact the model is surprisingly flexible. So if anyone in Cairn were to want a personal shareholding in some other operation, but to do so in partnership with Cairn, this can be done by the Trust having a stake in it as well. In fact it’s already happening in respect of our new Brexit-bashing German subsidiary, although that’s definitely a story for another time, albeit soon!

The basic Trust model has been in existence in the UK for many years, with both the Guardian newspaper and the John Lewis Partnership being particularly well known examples, but until recently the way to establish one seems to have been rather a well-kept secret. Fortunately that’s no longer the case, but our first attempt failed so spectacularly that if only for wry amusement the story is worth retelling here!

In this first attempt, we had been directed to some apparently specialist solicitors, who in turn introduced us to some people who claimed to be able to set a Trust up for us. However, although I felt this should have been pretty straightforward, things proceeded very slowly, but we were told that the person who was looking after this for us was also dealing with the affairs of a terminally ill client, which sounded fair enough. However, at the risk of sounding too flippant, that client did die, but also very slowly, and so also perhaps understandably our contact then took what may well have been a well-earned holiday. But the problem was that our contact then decided not to come back, so the task was passed on to someone else. Still ok under the circumstances I suppose, but when I told the new contact that I wanted something along the lines of the “John Lewis model”, he asked “What’s that?”. This was my cue to run away from these people as fast as possible!

So there things stood for a few years, as it looked as if this was all going to be more difficult than I’d expected. However, I then came across another organisation who did appear to know about such things, so I had expected to do something with them in due course. However, my personal financial affairs were complicated at the time by the poor health of my sister, as I related in a 2019 blog Although she had assets of her own, of course I wanted to make some personal provision for her if need be. However, when she died relatively suddenly in June 2019, this no longer became an issue, so I could now make correspondingly more concrete plans, the effect of which will be to ensure that the ownership of the farm can also be transferred to the Trust in due course.

By this time my contact in that other Company had moved on, but our financial adviser Dan Lamba did a bit of legwork for us, and directed us to the specialist Trust experts Postlethwaite

who together with Dan set up everything for us in a nicely straightforward way. Recent legislation seems to have made this type of process rather easier than it was only a few years ago, and now there is even an Employee Ownership Association to help you for advice before during and after you’ve taken the plunge. So if you are interested to know more, these are probably the only links you need.

CLOSING THOUGHTS – C’EST PLUS LA MÊME CHOSE!

Although this is in some ways a big change, in others it isn’t really a change at all! I’m going to stay living on the farm, and I’m going to stay doing things for Cairn. I’m also (surprise, surprise) going to be one of the Trustees, and I’m going to continue in my role of Chairman. However, the important point is that my involvement with Cairn is no longer critical for the continuation of the Company, so now I really can do whatever I want and go wherever I want.

So what DO I want? That’s a good question of course! The “problem” is that the farm has become such a great environment that I’d much rather stay here! In fact, there is a slight irony in that if there was one thing I could have changed, it would have been to live a bit closer to town, but the moral here is that you have to be careful what you wish for. This is now coming to pass, because the town is growing out to meet us! There used to be three clear fields between the farm and the eastern edge of the town, but a recent housing development means there are now only two, and if the latest proposed developments are approved, then soon there will be only one.

Of course I understand that people need somewhere to live, but I’m astonished by how small a house (we’re building the smallest ones in Europe) you can now buy for so much money. Compared with the now wonderfully renovated farmhouse, those new ones just down the road do look a bit on the small side, but then I realise that I’m looking at a pair of semis. Ouch! So why on EARTH would I want to leave here, especially when it’s only a thirty minute walk to town via a nice footpath?

But a bit more travelling would be nice of course. As part of my reaction to Brexit (Brexit “done”??? – it has barely started!), I am using my Irish ancestry to apply for Irish and hence to regain EU citizenship. For that I had a very interesting time researching into my Irish connection but thanks to the disruption of Covid, the processing of applications has been much delayed, so for now I’m still merely British. Hence I find I’m waiting for that EU passport before I do consider going anywhere, but as of writing (November 2021) the world has perhaps still not gone sufficiently back to normal for international travel to be so appealing. In this respect too, the farm is proving to be rather too nice an environment!

CAIRNLAND

However, as another antidote to Brexit, I did have fun a while back writing a satirical series of articles, in which our farm had declared independence from the UK as Cairnland

All articles available here – [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]

in order to remain in the EU, but eventually I had to call a halt, as time and again the reality seemed to out-satire whatever I managed to come up with. But the underlying point is that of course we want Cairn to be seen as an internationally oriented Company, and in order to facilitate our EU sales in particular, then as already hinted in the previous section, we’ve just set up a German subsidiary for this very purpose – so please look out for further details very soon!

And so yes, I also fully intend to continue “working”, but the fortunate truth is that for me, it has rarely seemed like work at all. I’ve always found designing and building things (whether they are new products or new farm buildings!) to be great fun, so I might as well continue to do so for Cairn, rather than developing some other sort of hobby.

So here, finally, we are edging towards that seventh principle. If I can have fun doing all this, why can’t the others at Cairn too? I’m not so naive as to expect everyone here to always find it as pleasant an experience as I have, but nevertheless I do think this is a goal that we should aspire to. For years I’ve been reminding everyone that we don’t have outside investors or some central office to placate, so let’s try not to act as if we do! Whereas of course the “pressure to conform” to those norms is always at least subconsciously there, so we always need to close our ears to those siren calls, and hence I do find myself handing out the ear defenders from time to time.

This is why I hope that our new Trust structure will act as a continuing reminder that we can do things the way we want to, rather than the way that we feel we ought to. And we’re certainly off to a flying start! We’ve come through Covid in excellent shape, with our coffers and our order book both nicely full, so right now we’re much more concerned about getting the work out than the money in, and long may that situation continue of course (although being just a little bit less busy right now would be nice).

Concerning the conducting of the business in general, the main thing I’ve learned on this account is that if you ever try to do anything new (which of course you should), it always tends to take longer and cost more than you expected. However, if your efforts are successful, then whatever you have developed tends to sell in larger quantities and to have a longer commercial lifetime than you expected, so if you hold your nerve it more than balances out! And the part of this situation that I particularly like is to see a lot of such “repeat” business regularly coming in, as it provides a nice regular income stream to counter the regular outgoings that any business must inevitably cover.

OPTOSPINS

So those Optospins, for example, that took me so much time and effort to develop, are now very seriously paying their way. From being a “problem child” for a while, they have now become another “cash cow” for us. And of course I’m not the only person doing this sort of thing. Other notable and relatively new Cairn products such as Tom’s OptoTIRF, and Jez and Callum’s openFrame modular microscope, which was developed in collaboration (yes, that one certainly worked!) with Paul French at Imperial College, are also looking very promising, and I had nothing to do with these at all!

The moral here is to make sure that people have the time and space to make a success of whatever they are trying to do. We’ve always tried to adhere to this principle, and the Trust model will ensure that we can continue to do so.

Well, finally I reckon we’ve got to that seventh principle, which may indeed be the most important one for the long term continuation of a business. The development of successful products is a rewarding activity in itself, as it does give a genuine sense of achievement. And I strongly believe that people do their best work when they find it to be rewarding, and also when they feel empowered to carry it out in whatever way they think best. Nobody knows more about a project than the people who are actually carrying it out, so the management process must be at least as much about listening as talking. I’m not saying we always get this right, as we are all only human, but I think we do at least try!

So what exactly does that ultimately vital seventh principle come down to, and that the Trust will help us continue?

7. Do your best to ensure that everyone is enjoying what they do!